Practical Tips for Conducting Credible Investigations

1. Know when tips, rumors, or allegations require an

investigation, even if the informer wishes to remain anonymous, and

what can be ignored. Allegations of an inappropriate relationship

with a student by a school employee or threats to student safety

always warrant investigation.

2. Documenting a complaint is the foundation on which an

investigation rests. Avoid telling the complainant the complaint

must be put in writing for you to do anything and assist, when

receiving a verbal complaint or conditions warrant, in preparing a

written complaint.

3. Take time to plan the investigation, as failure to do so can

enable people to cover their tracks. There are many ways to

approach an investigation, depending on the nature of the

complaint, e.g., personnel, parent, student, sexual misconduct, or

discipline issues, all with varying degrees of seriousness, and no

one way works in all situations.

4. Consider whether/when to involve other agencies, such as law

enforcement or DFACS, and the possibility that they may claim they

were not notified in a timely manner or that the investigation

interfered with their investigation.

5. Identity the existing records or documents that may contain

relevant information and get them immediately, before talking to

witnesses; otherwise, documents may go missing. Plan to secure

written consent where required.

6. Identify other individuals who may have corroborating evidence.

Resist the feeling of urgency to go immediately to the accused or

the complainant or to bring them together.

7. Decide which witnesses must be interviewed and in what order,

balancing decisions with available time, which is usually limited.

It usually is best to talk first to the most candid and most

reliable witness because once the first person is interviewed,

other potential witnesses probably will know the information and

questions asked.

8. Before the interview, outline the questions to be asked,

recognizing that spontaneity is necessary to follow up on answers

received.

9. Decide when to begin the investigation. Consider the risk of

starting on Friday afternoon and continuing on Monday, as long

weekends can change an investigation.

10. Decide who will conduct the interviews, considering who is

likely to be the most productive in getting the information.

Whether central office personnel or the superintendent need to be

involved in interviewing depends on the seriousness of the

allegation and its potential for ending up in litigation. Although

the board attorney may be consulted throughout the process,

reconsider the urge to have him/her conduct the interviews, as

his/her involvement in that capacity could result in later

disqualification from representing the district or an argument that

the attorney's interview notes are discoverable by an opposing

party.

11. Decide who will witness the interviews as backup for the

interviewer. Generally, it is not a good practice to use a peer

teacher as a witness when a teacher is being investigated or for

the principal to use his secretary. The accused is not entitled to

have an attorney/advisor present unless law enforcement is

investigating a crime. Students are not necessarily entitled to

have parents present, but they should be informed/involved as soon

as possible depending on the facts in the specific case.

12. Remember that recording witness interviews can be a two-edged

sword that may be used against the district, as it will be

available to the other side in an adversarial situation.

13. Emphasize the confidentiality of the investigation and warn

against retaliation against the accused, the complainant, or any

other witness. Do not deceive witnesses by telling them that

information disclosed will not be disclosed to anyone else. Make

clear that you are not asking anyone to take sides; all they need

to do is tell what their eyes saw and their ears heard.

14. Resist the temptation to bring in a student with instructions

to write down what happened. Consider a technique in which the

administrator, with no notes or recorder, encourages the student to

tell the story from beginning to end. Once the story is out, the

interviewer drafts a coherent summary statement written in the

first person, allows the student to read/correct it, and gets the

student to add a statement such as "I affirm this is a true

statement," accompanied by the signatures of the student and a

third party who witnessed the interview.

15. Do not make statements during the interview that express an

opinion one way or the other, as sympathetic listening can be

misinterpreted as witness support that may come back to haunt the

interviewer.

16. It is generally better to gather all relevant information from

other witnesses before interviewing the accused so that there will

be a frame of reference for evaluating the testimony of the

accused. Decide in advance what information obtained from witnesses

will be disclosed to the accused.

17. When interviewing the accused, avoid giving advice or making

threats. Start with general questions and narrow them down to

specific facts that are alleged. If the accused admits to the

allegations, be prepared with options available to the accused. If

the accused denies the allegation, put that in the statement.

18. Be sure that interview or other investigation documents are

properly identified and dated.

19. Document the process, regardless of whether the investigation

is conclusive or otherwise, to protect the district from later

allegations that administrators knew and did nothing. Avoid telling

the complainant that there is no evidence. If there is no

conclusive evidence, there should be statements from witnesses that

led to that conclusion.

Decide what type of report, if any, should be produced detailing

the investigation results and any recommendations the investigator

may have, remembering any privacy or disclosure rights that may

exist under the Georgia's Open Records Act or the Family

Educational Rights and Privacy Act

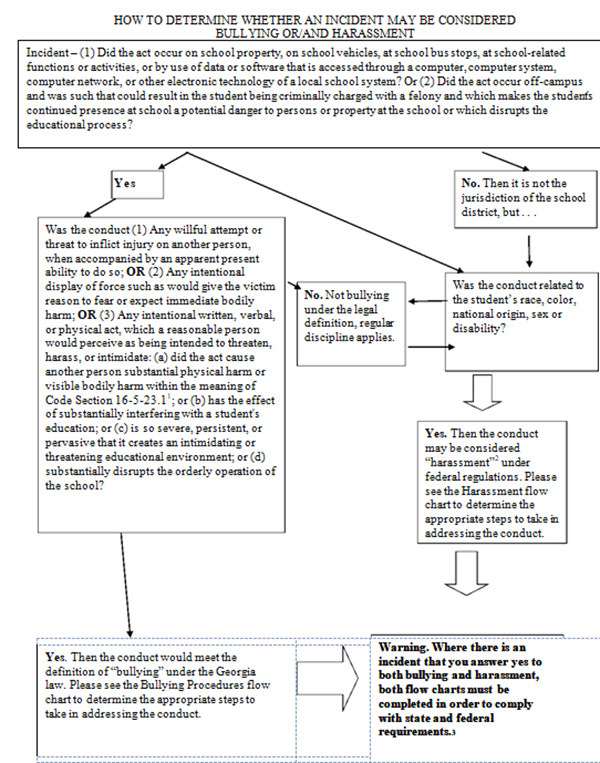

1. O.C.G.A. § 16-5-23.1 - Definition of battery. A person commits the offense of battery when he or she intentionally causes substantial physical harm or visible bodily harm to another. As used in this Code section, the term 'visible bodily harm' means bodily harm capable of being perceived by a person other than the victim and may include, but is not limited to, substantially blackened eyes, substantially swollen lips or other facial or body parts, or substantial bruises to body parts.

2. According to the October 26, Dear Colleague letter, OCR's position is that harassment with motive based on "any actual or perceived characteristic including race, color, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, ancestry, national origin, physical attributes, socioeconomic status, physical or mental ability or disability, or by any other distinguishing characteristic" can be investigated by OCR.

3. When starting an investigation, consider if you need others to be involved, including DFACS or law enforcement and possibility special education staff. Further, it may be necessary to include other administrators based on the severity of the incident and who may be best to interview certain witnesses.